Custom in the background

Even where French legal categories govern the formal outcome, local expectations can influence what parties view as “fair”, “respectful”, and durable—especially where elders and extended family are involved.

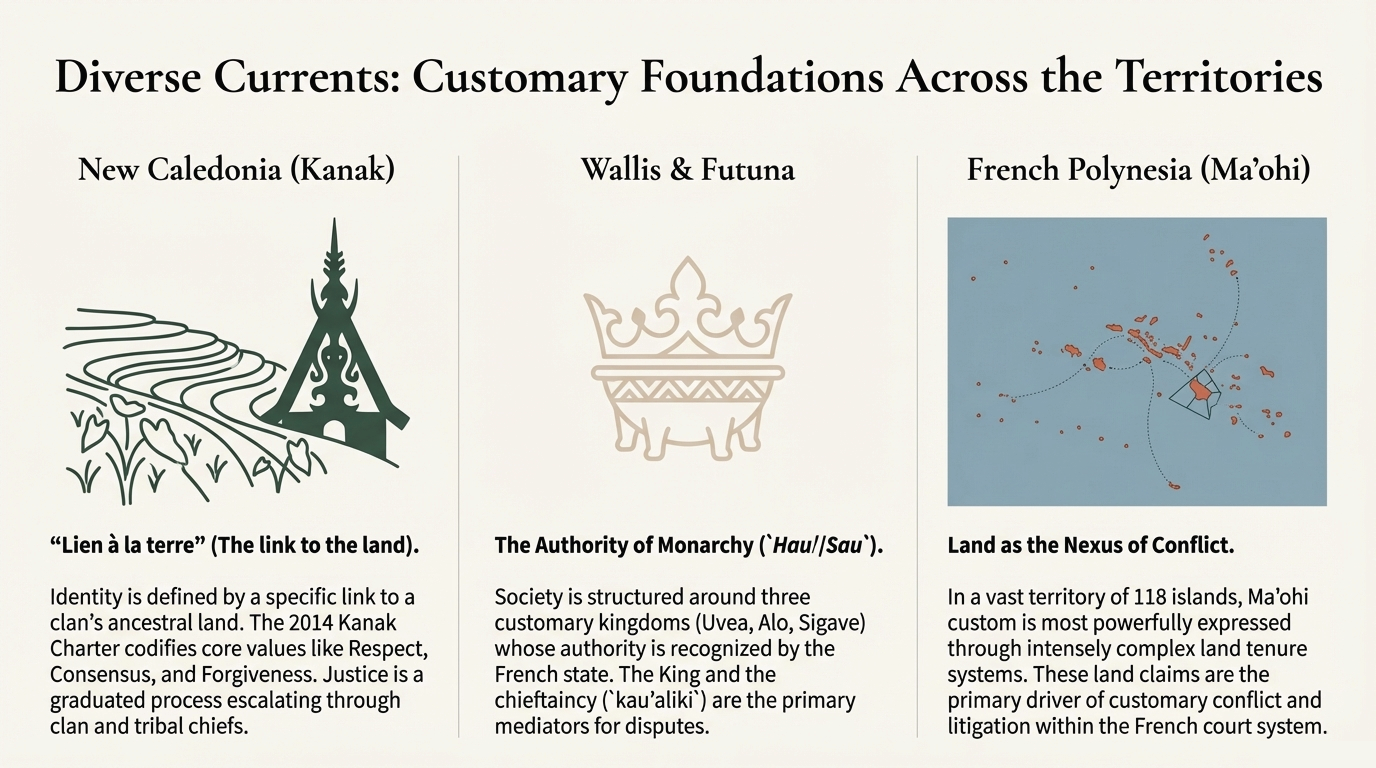

French Polynesia sits within the French Republic, yet local dispute resolution is shaped by a continuing Ma‘ohi relationship to land, genealogy, and community obligations. The result is a distinctive legal pluralism where French courts and state ADR operate alongside (and are influenced by) customary expectations.

French Polynesia is an autonomous “Overseas Country” with significant local legislative capacity, but French national law remains applicable. The most persistent disputes commonly revolve around land tenure and succession, where history and genealogy matter as much as documents.

This interface often produces long-running conflicts, as families navigate competing narratives about ownership, inheritance, and belonging—while seeking outcomes that will hold social legitimacy as well as legal finality.

For mediators and lawyers, the central practical question is how to design processes that respect collective identity and history, while still meeting the procedural expectations of the formal system.

While Ma‘ohi customary structures are not as formally integrated into state courts as in some other French territories, customary influence remains strong—particularly in land tenure and succession.

In many disputes, land is a repository of family history and legitimacy. Claims and counterclaims can depend on whakapapa-style genealogical accounts, oral histories, and community recognition, not simply on titles.

Even where French legal categories govern the formal outcome, local expectations can influence what parties view as “fair”, “respectful”, and durable—especially where elders and extended family are involved.

Land and inheritance disputes can disturb relationships across households, not merely between two individuals, increasing the importance of careful process design and staged agreements.

The report highlights that French Polynesia’s most significant customary influence is felt in land tenure and succession claims, which can be complex, historically rooted, and protracted.

In practice, a durable settlement often blends legal clarity with relational repair (recognition, apology, or agreed family governance arrangements).

Make time for narrative accounts, genealogy, and agreed factual anchors before bargaining about outcomes.

Explain what the Land Tribunal can and cannot do, and how evidence will be treated if mediation fails.

Use “who does what next” plans—registrations, consents, succession steps, and agreed family protocols.

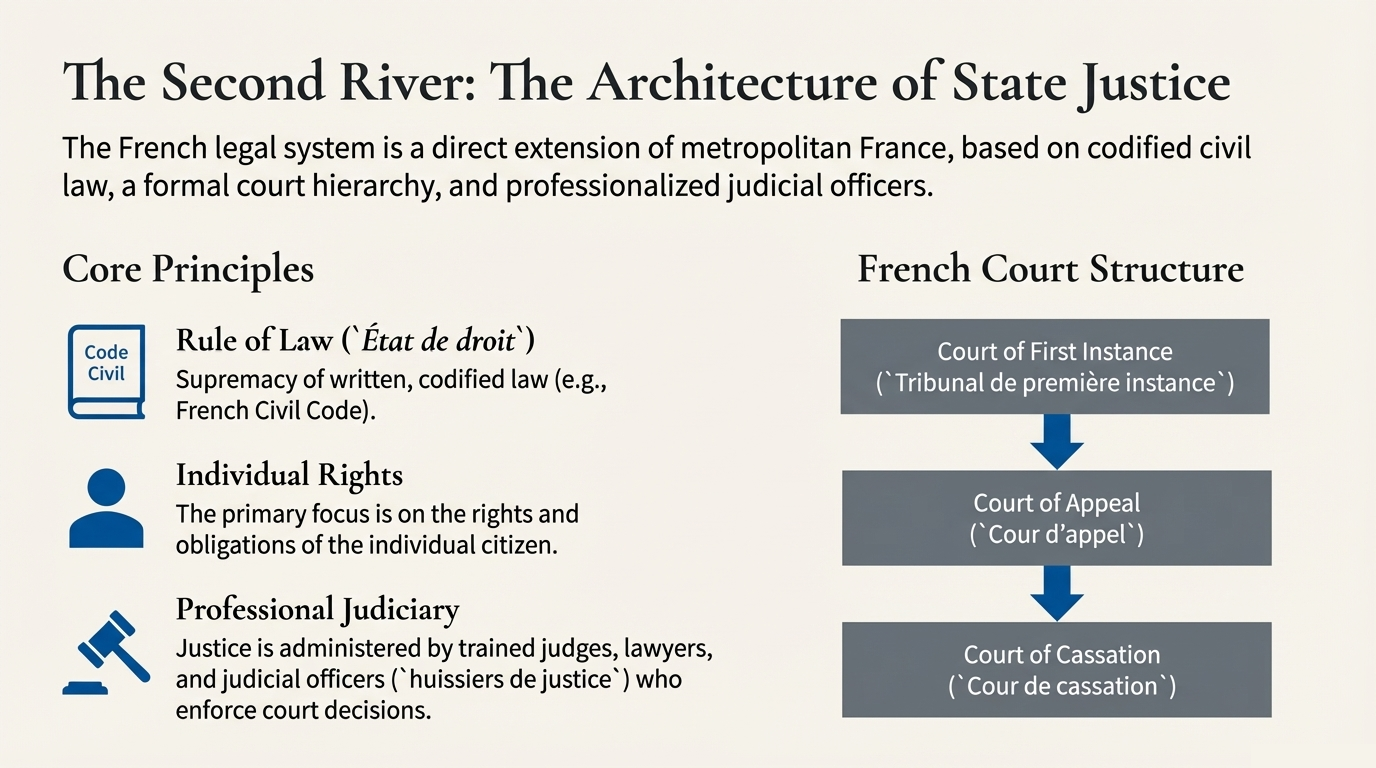

French Polynesia has a highly professionalised formal judiciary (including a Court of Appeal in Papeete) and a specialised Land Tribunal reflecting the prevalence of land-related disputes.

French national law (including the Civil Code and Criminal Code) applies, with local adaptations through the territory’s constitutional status and organic/territory-specific instruments.

The formal system can deliver legal certainty, but may struggle to address the relational and identity dimensions of disputes that sit behind many land and succession conflicts.

A distinctive feature is the regulated profession of “land mediators”, with legal qualifications and specialised training. Local law requires an attempt at mediation before land claims proceed to the Land Tribunal—embedding ADR as a mandatory pre-litigation step.

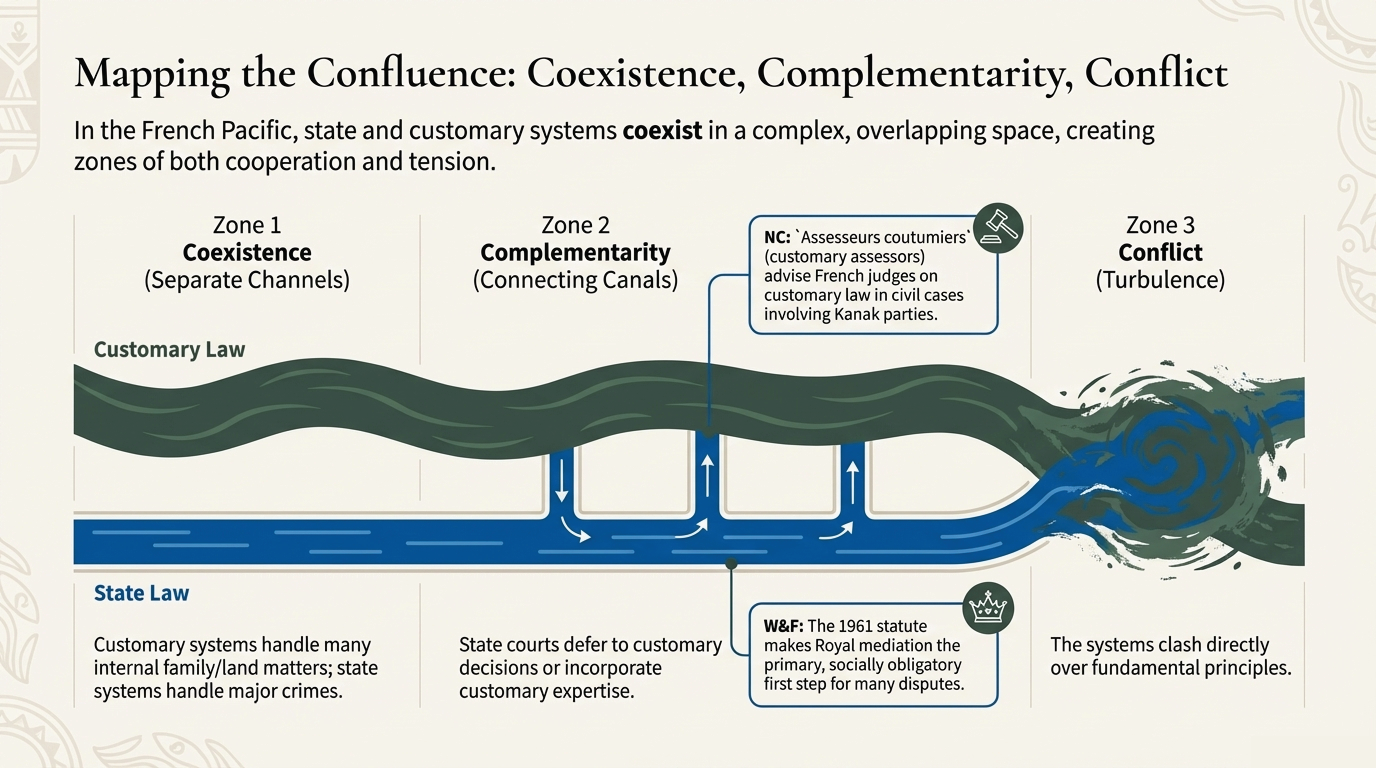

The relationship between customary influence and French law is not a clean division. It is a practical negotiation shaped by the territory’s autonomy, the lived centrality of land, and the institutionalisation of mediation for land matters.

Compulsory land mediation functions as a bridge between social legitimacy and formal legality.

Land tenure and succession remain a primary driver of complex disputes that can be multi-generational.

Local autonomy creates room for tailored mechanisms—while French law provides the overarching structure.

The practical divide is often less about “custom vs court” and more about what each system is designed to do: relational legitimacy and shared history, versus authoritative legal determination.

| Feature | French Polynesia (land & customary influence) | Western / Australian mediation baseline |

|---|---|---|

| Typical dispute engine | Land tenure & succession with deep genealogical history and multiple claimants. | Private civil disputes framed around immediate parties and defined legal rights. |

| Process legitimacy | Often requires narrative, recognition and family buy-in to “hold” socially. | Legitimacy driven by confidentiality, neutrality, and party self-determination. |

| Institutional pathway | Compulsory land mediation before Land Tribunal (state-backed ADR as confluence). | Mediation commonly voluntary (or court-ordered), but not always a mandated gateway. |

| Outcome focus | May need governance-style solutions: shared use, succession planning, protocols. | Written settlement focused on enforceable rights/obligations and finality. |

In land and succession disputes, the mediator’s task is often to translate between narratives of belonging and the evidentiary demands of the Land Tribunal—without reducing the dispute to paperwork alone.

A short video will accompany this page. You can paste the embed code into the block below when ready.

French Polynesia demonstrates how state institutions can create a “meeting place” for disputes that are social, historical, and relational—particularly through structured land mediation before litigation.

For practitioners, the practical goal is not to force a single model, but to design a pathway that honours collective identity and narrative while providing clear legal steps. Land disputes, in particular, benefit from agreements that integrate governance and implementation: who will do what, by when, with which documents, and how the family will live with the arrangement.

When these elements are addressed early, the “two rivers” can become a braided confluence—stronger, clearer, and more durable than either approach alone.