Centre kastom and wantok

- Assume kastom and wantok obligations are central, not peripheral.

- Design processes that work with, not against, existing community forums and leaders.

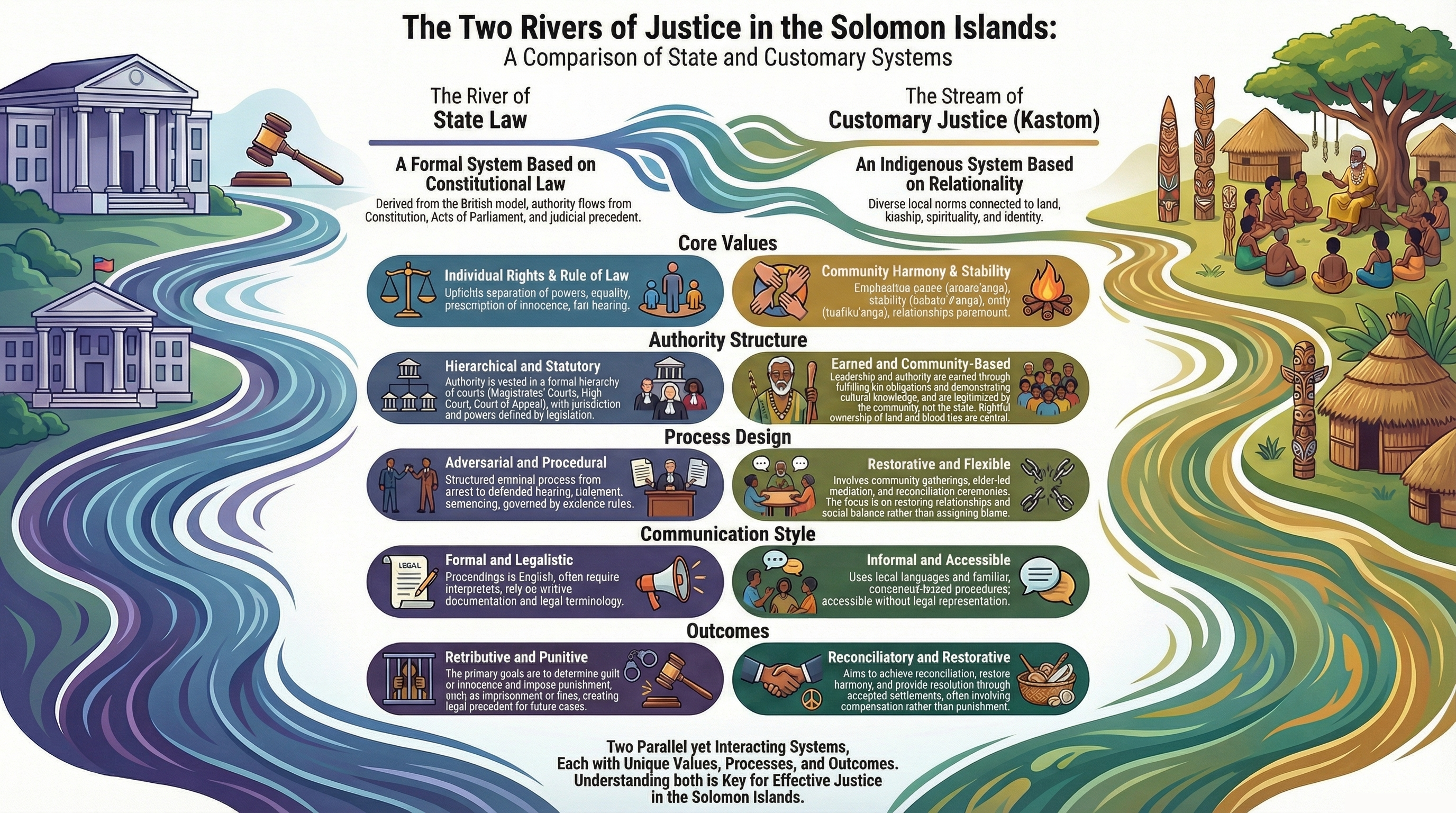

In Solomon Islands, justice flows through two powerful streams: a constitutional state system modelled on Westminster, and kastom – relational, wantok-based practices that place community harmony above individual rights. For most citizens, especially outside Honiara, kastom remains the primary and most trusted source of order.

This short video introduces the dual justice landscape of Solomon Islands: kastom processes rooted in place and kinship, and a formal state system that is often “paper strong but practice weak”. Use it as an accessible primer before engaging with the full report or slide deck.

Understanding dispute resolution in Solomon Islands begins with its socio-cultural foundations. Identity is anchored in ancestral islands, land and kin – captured in the Kwara’ae concept of Ngwae ni fuli, “person of place”, rather than abstract citizenship.:contentReference[oaicite:1]{index=1}

The archipelago is diverse, but most people see themselves first as members of particular language and kin groups. National identity is comparatively weak, and the formal state plays a limited role in everyday life, especially beyond Honiara. Customary and church-based structures carry greater practical authority.

The modern justice landscape is also shaped by the civil conflict from 1998–2003, known as “the Tensions”, which saw violence between communities from Guadalcanal and Malaita and the manipulation of traditional practices like compensation for political and criminal ends.:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}

Contemporary conflict-resolution practices are anchored in wantok obligations, communal peacemaking and narrative dialogue, all reshaped by colonisation and the Tensions.:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}

The wantok system (“one talk”) is a dense network of mutual support and obligation among those who share language and kin ties. It underpins accountability and social safety nets but also fuels nepotism and patronage that can undermine formal institutions.:contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}

Traditional peacemaking emphasises community meetings, reconciliation ceremonies, and compensation – historically in pigs, shell money and other valuables, increasingly in cash. A distinctive communicative practice is tok stori, a discursive, group-based conversation style that allows narrative, indirect communication and collective problem-solving.:contentReference[oaicite:5]{index=5}

During the Tensions, these practices were distorted: compensation became a tool for extortion, feeding competition between claimants and contributing to what analysts describe as the “progressive criminalisation” of the state. Women and church groups nonetheless played quiet but crucial roles in peacemaking, crossing militia lines to build trust and open space for formal negotiations.:contentReference[oaicite:6]{index=6}

Customary mechanisms aim first at restoring social balance. Disputes are community affairs, not private grievances, and processes are led by figures of inherent authority rather than neutral mediators.:contentReference[oaicite:7]{index=7}

Chiefs, elders and religious leaders convene meetings, guide discussion and recommend outcomes. Their authority flows from status, wisdom and kin connections. The focus is on reconciliation, apology and compensation rather than formal findings of guilt.

Proceedings are usually public or semi-public. Community members witness apologies and compensation exchanges, providing social validation and an enforcement mechanism through collective expectations.

Solomon Islands’ formal system follows a Westminster model but operates in a context where kastom and church often command greater allegiance. The Constitution nonetheless gives customary law a prominent place in the legal hierarchy.:contentReference[oaicite:9]{index=9}

The Court of Appeal, High Court and Magistrates’ Courts form the core structure, supplemented by Local Courts and Customary Land Appeal Courts mandated to hear matters involving customary land. The Constitution and the decision in Igolo v Ita place customary law above received English common law and statutes of general application.:contentReference[oaicite:10]{index=10}

State-sanctioned ADR remains thin. Judges encourage settlement in civil cases but formal mediation frameworks are limited. Section 35 of the Magistrates’ Courts Act allows reconciliation in certain minor criminal matters. After the Tensions, the state created the National Peace Council (NPC) to support inter-communal mediation and reconciliation.:contentReference[oaicite:11]{index=11}

Several key statutes explicitly defer to custom in family and property matters, including marriage, divorce, wills and customary land, reinforcing the formal recognition of kastom in the legal order.:contentReference[oaicite:12]{index=12}

Kastom and state law are formally recognised as twin sources of authority, but the relationship is marked by parallel operation, hybrid innovation and sharp points of friction, particularly around human rights and the manipulation of custom.:contentReference[oaicite:13]{index=13}

Citizens often decide whether to engage the courts or rely on kastom and church. When state directives clash with kastom teachings, many default to the latter, preferring symbolic reparations that repair relationships to court-based processes that feel distant and punitive.:contentReference[oaicite:14]{index=14}

Hybrid models, such as the NPC’s peace work, have blended shuttle mediation with kastom ceremonies, harnessing the authority of chiefs to legitimise outcomes. The state itself has also used compensation – a kastom tool – as a key mechanism under the Townsville Peace Agreement.

Courts have sometimes prioritised constitutional rights over custom, for example granting custody to mothers where kastom would favour fathers, and questioning the use of reconciliation alone in domestic violence cases when it leaves victims without meaningful sanction or protection.:contentReference[oaicite:15]{index=15}

At the same time, kastom can be instrumentalised. During the Tensions, compensation practices were distorted into tools for extortion and political patronage, fuelling further disorder and undermining both traditional and state justice. Women are frequently marginalised from decision-making, especially in land disputes.:contentReference[oaicite:16]{index=16}

For practitioners trained in Australian or Western mediation models, Solomon Islands offers a contrasting paradigm: collective, public and authority-led, rather than individualised, confidential and neutral-facilitator-centred.:contentReference[oaicite:17]{index=17}

| Feature | Kastom / local practice | Western / Australian mediation |

|---|---|---|

| Core values | Collective harmony, restoration of relationships and fulfilment of wantok obligations; group well-being takes precedence.:contentReference[oaicite:18]{index=18} | Individual autonomy, self-determination and satisfaction of personal needs and interests. |

| Third party role | Chiefs, elders and church leaders with directive authority; they guide discussions and may propose or decide outcomes. | Neutral facilitator with no stake in the outcome and no decision-making power; manages process only. |

| Process design | Organic, communal and public; often includes rituals and compensation ceremonies marking restored peace.:contentReference[oaicite:19]{index=19} | Structured, confidential and stage-based (opening, exploration, negotiation, agreement). |

| Key concepts | Confidentiality is rare – disputes are community matters; neutrality is replaced by respected authority; voluntariness is shaped by strong social pressure to reconcile.:contentReference[oaicite:20]{index=20} | Confidentiality, neutrality and voluntariness are core principles and ethical requirements. |

| Communication style | Indirect, narrative and collective; tok stori emphasises story, listening and group conversation. | Direct, interest-based conversation with emphasis on clear articulation of issues and interests by each party. |

| Outcome formation | Public, restorative outcomes endorsed by the community, often including compensation and ceremony. | Private, written agreements between parties, typically future-focused and enforceable as contracts or consent orders. |

Effective cross-cultural practice requires humility and flexibility. Practitioners should aim to co-create hybrid processes that respect kastom while engaging with human rights and professional standards.:contentReference[oaicite:21]{index=21}

Solomon Islands demonstrates both the resilience of kastom and the fragility of formal institutions in a context where the state is still building legitimacy. Future progress will depend on creative, hybrid approaches that braid these two rivers of justice together.:contentReference[oaicite:22]{index=22}

Key tensions – between kastom and human rights, solidarity and nepotism, tradition and manipulation – will not disappear. But examples like the National Peace Council show that carefully designed hybrids can harness local authority and external tools to address serious conflict.

For external practitioners, the challenge is to step away from exporting ready-made models and instead act as culturally literate facilitators, co-designing processes that communities recognise as their own.

In that sense, working in Solomon Islands is less about mastering another technique than about learning to “fly with two wings”: state law and kastom, held in creative tension.