Acknowledge authority and protocol

- Identify who has cultural authority to speak for Country and kin.

- Engage Elders early and with appropriate respect and consent.

- Do not assume Western neutrality is always the highest value.

Exploring how Australia sits at the confluence of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander customary law and the Australian state legal system, and what this means for justice, authority and legal practice.

This video introduces the Australian study within the Two Rivers of Justice project, outlining how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander customary systems of Law interact with the Australian common law and its courts and ADR institutions.

Replace the embed ID in the frame with the final video for Module 2: Australia when it becomes available.

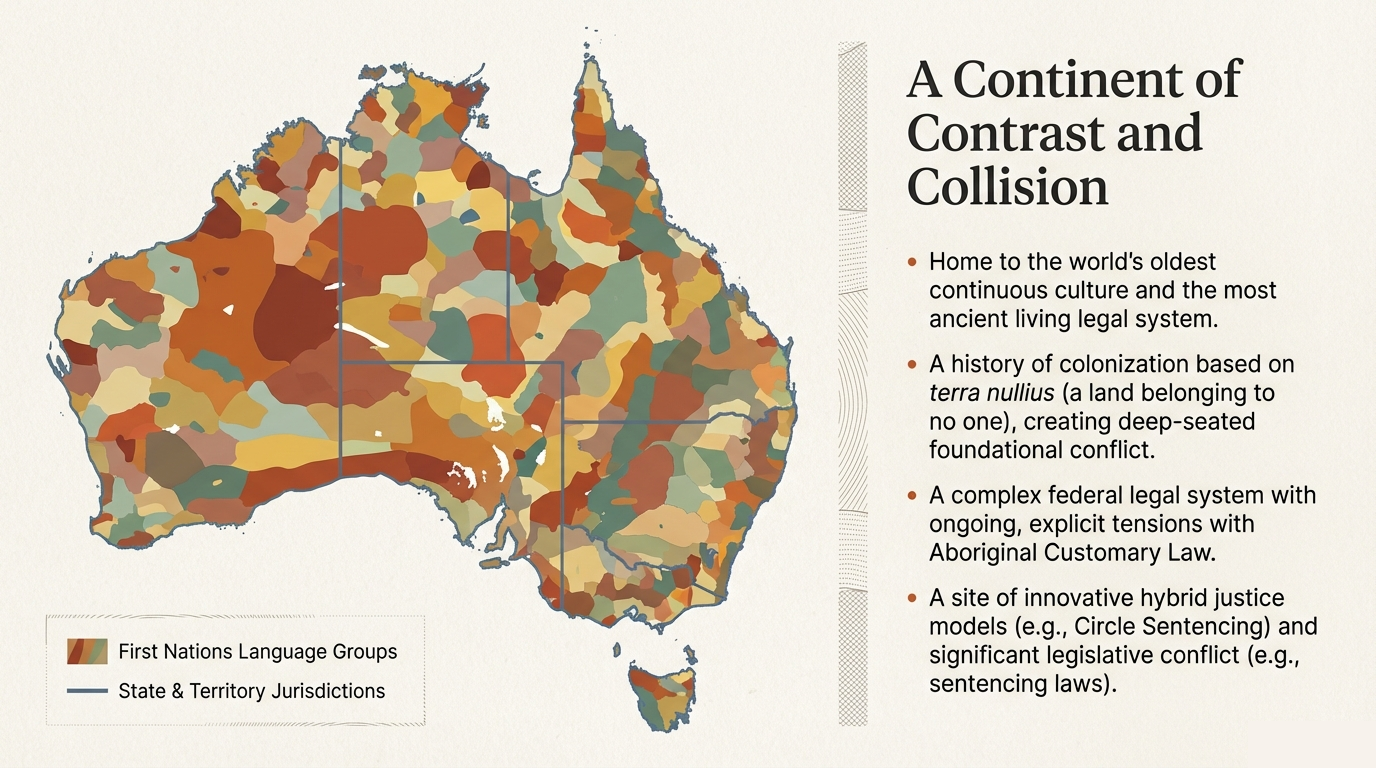

Australia is home to the world’s oldest continuous cultures and a complex federal legal system built on British common law. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples navigate both the Laws of Country and the institutions of the modern state.

The formal Australian legal system emphasises individual rights, adversarial procedure and written legislation, with mediation and other ADR processes now resolving the vast majority of civil disputes before a court hearing is reached.

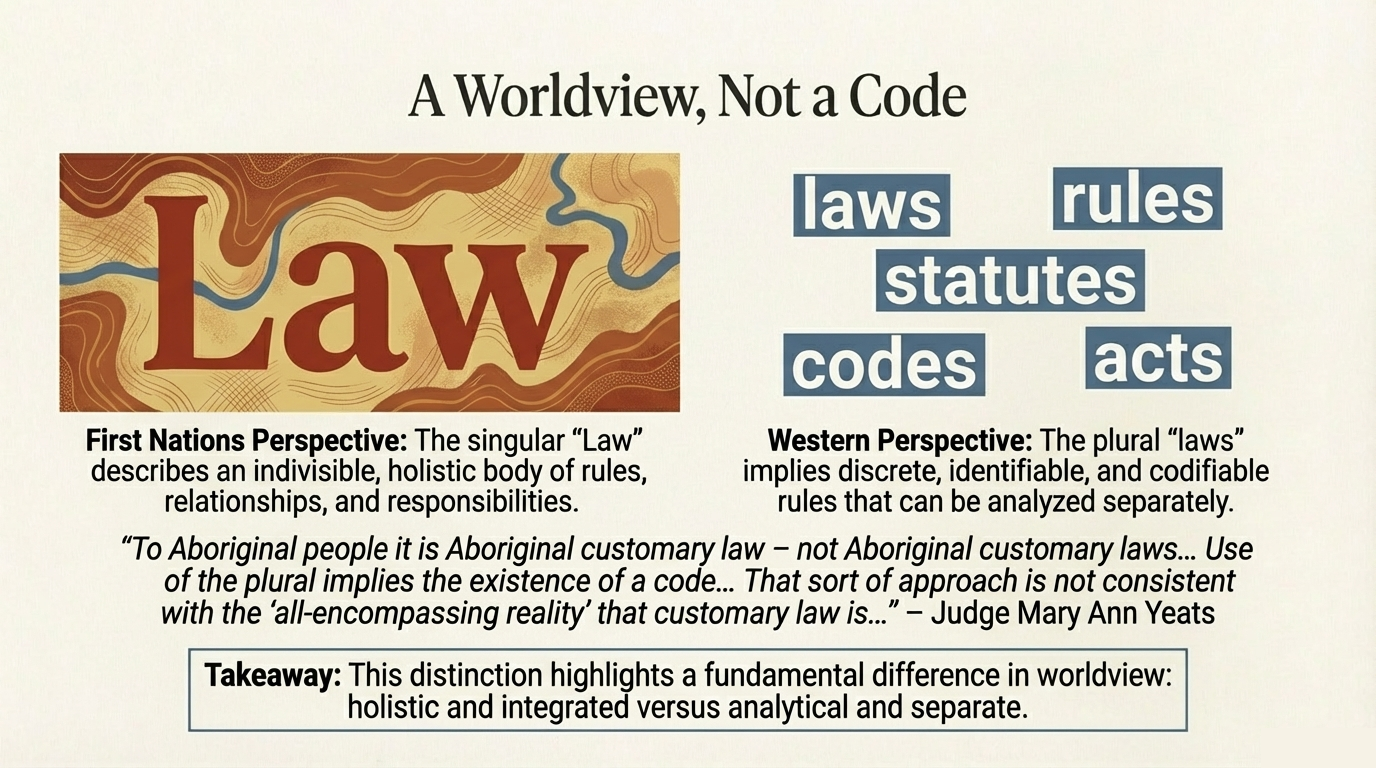

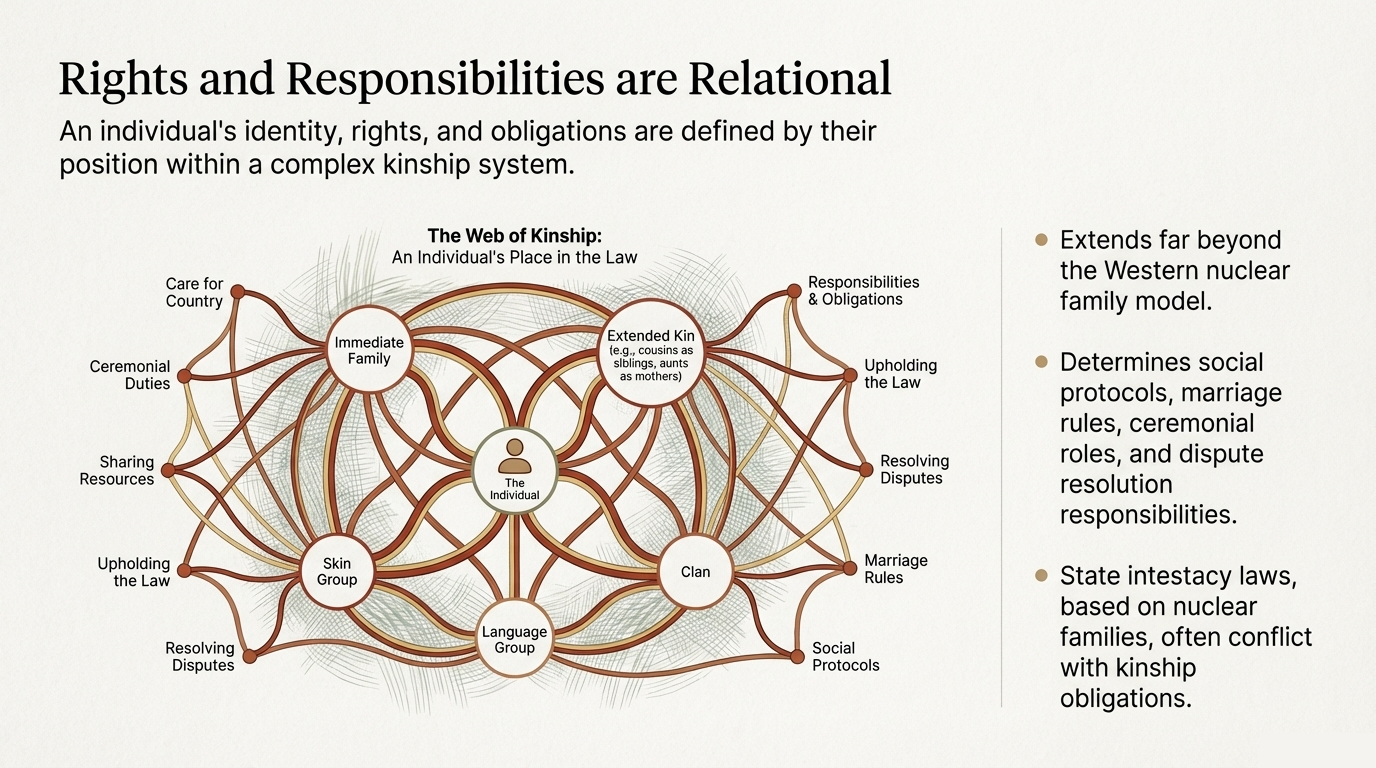

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, by contrast, customary law remains the primary framework governing relationships, responsibilities and conflict. These parallel systems create a lived reality of legal pluralism, in which many people are bound by obligations under both rivers of law.

AUS is used for

Australia, including in asset paths and report filenames.

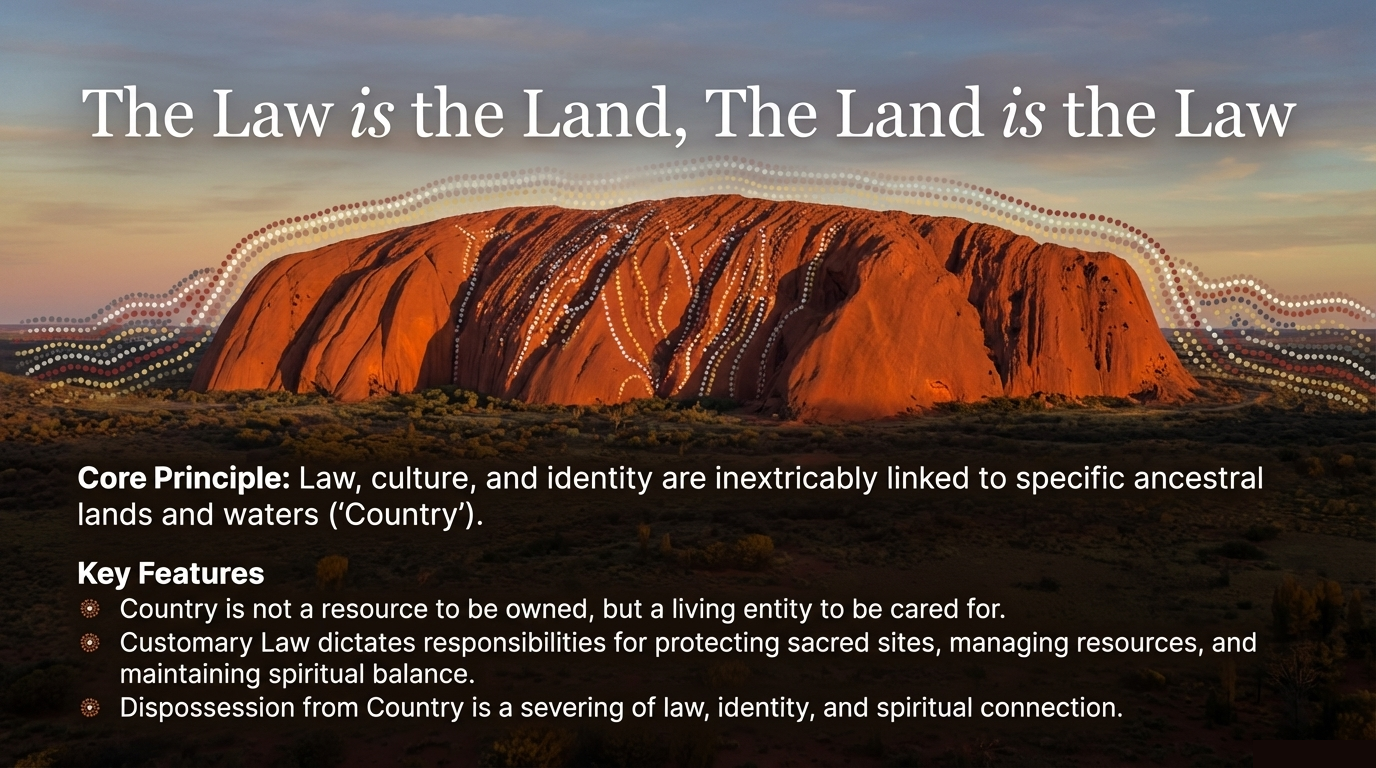

Australia’s current legal arrangements are shaped by colonisation without treaty, the legal fiction of terra nullius, later recognition of native title and an unfinished conversation about sovereignty and Makarrata.

British colonisation introduced a unitary sovereignty that denied existing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander laws and institutions. The doctrine of terra nullius treated the continent as legally “empty”, allowing imported common law to apply as if no prior legal orders existed.

Landmark developments such as the Mabo decision and subsequent native title legislation have acknowledged continuing First Nations relationships to Country, yet Australia still lacks a national treaty settlement, and customary law remains only partially recognised within the state system.

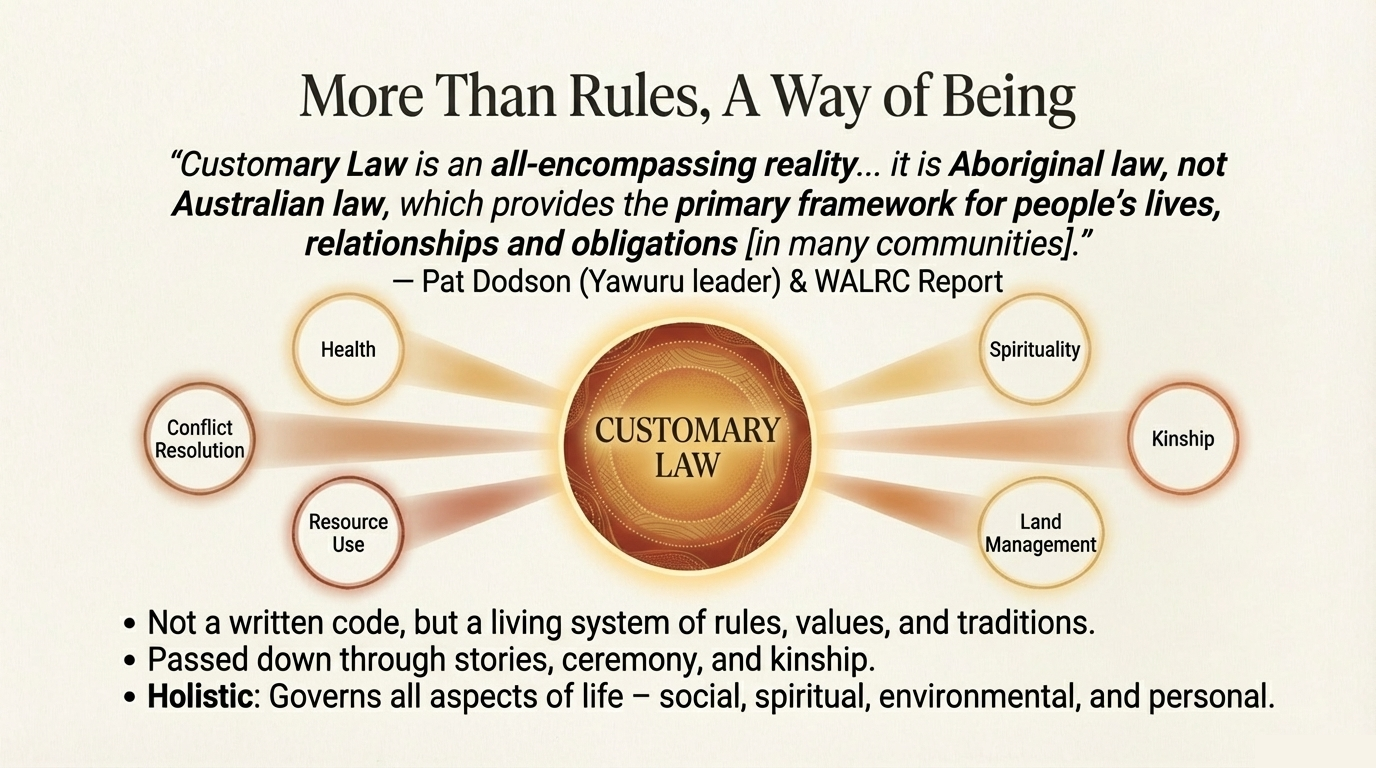

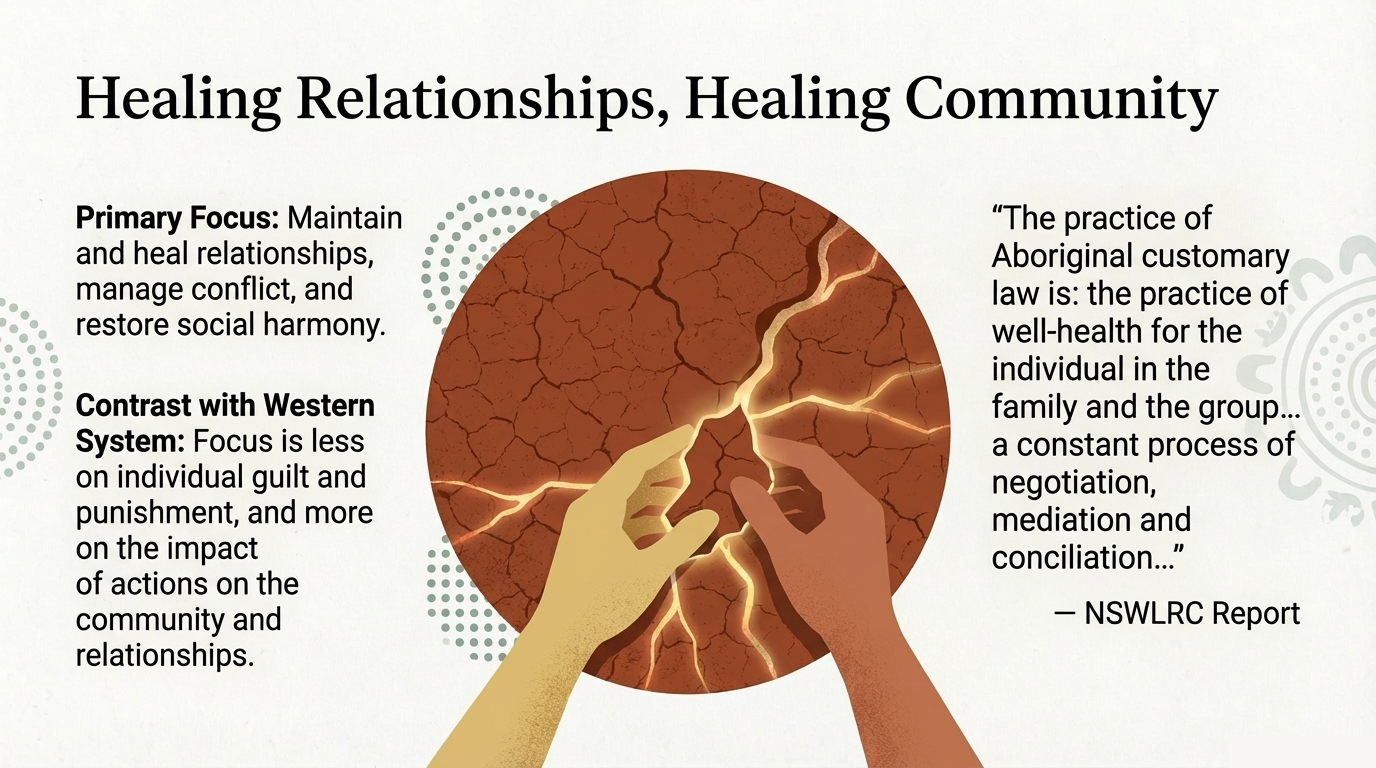

Indigenous dispute resolution in Australia is grounded in kinship, spiritual connections to Country and ancestral Law. It aims to restore balance rather than simply allocate blame.

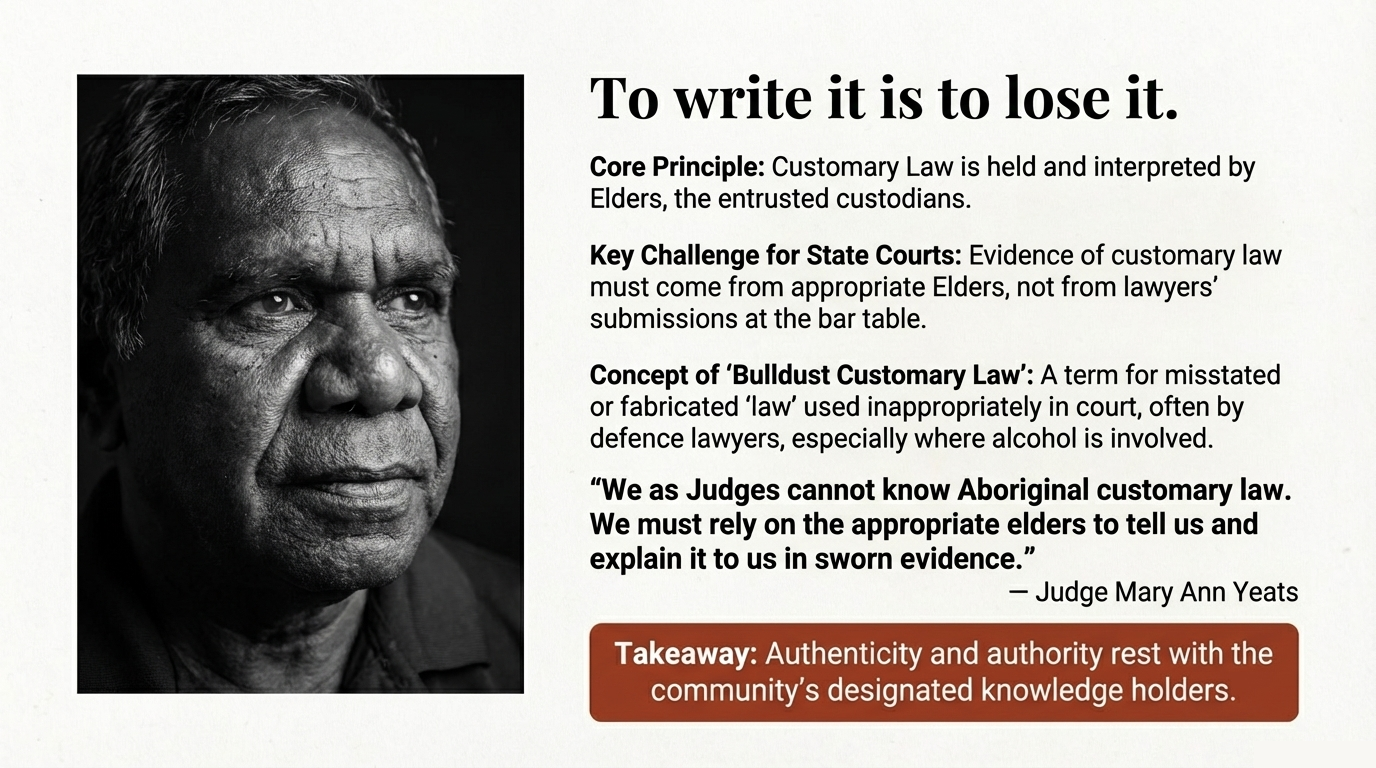

For many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, Law comes from the Dreaming. It is a living system of obligations, stories and ceremonies that defines how people live on Country, relate to one another and address wrongdoing. Elders and other recognised leaders hold authority to interpret and apply this Law.

Conflict is understood as a disturbance of relationships within extended kin networks rather than a purely individual problem. Processes for addressing that disturbance are structured and purposeful, even when they look unfamiliar through a Western lens.

Ceremonial reconciliation processes such as the Mawul Rom initiative draw on ancient forms of Law to address contemporary disputes. They weave together apology, ritual, storytelling and community affirmation in ways that a written agreement alone cannot replicate.

These practices illustrate how customary law continues to adapt and how it can inform modern, culturally grounded mediation and peacebuilding.

The Australian state legal system is a layered common law order with federal, state and territory jurisdictions, extensive use of ADR and persistent over-representation of Indigenous peoples in criminal and child protection systems.

The system includes the High Court, federal courts and state/territory courts, operating in an adversarial mode. Judges and magistrates apply legislation and precedent to determine outcomes, and procedure is framed around individual rights and responsibilities.

Legislation such as the Civil Dispute Resolution Act 2011 encourages parties to attempt resolution before commencing proceedings. Fewer than a small fraction of civil matters proceed to a full trial; most are settled through negotiation, conciliation or mediation.

Mainstream mediation in Australia is typically facilitative and structured into stages: introduction, story-telling, agenda setting, negotiation and agreement. Mediators are required to be neutral and to focus on helping parties reach a mutually acceptable, usually written, settlement.

Customary law and state law coexist in Australia, but they are not treated as equals. Recognition is selective, and conflicts between the systems are most visible in sentencing, land rights and family relationships.

Customary law is acknowledged in areas such as native title and, in some jurisdictions, succession and intestacy. Specialist forums — including Koori Courts, Murri Courts and circle sentencing — incorporate Elders and community voices into state processes without formally applying customary law as law.

At the same time, federal sentencing provisions prohibit courts from treating customary law or cultural practice as a reason to excuse, justify or reduce criminal responsibility. This produces a patchwork in which custom is welcomed when it aligns with state objectives but sidelined where it could disrupt uniform application of statute and precedent.

Individuals may face consequences under customary law (such as community-led reconciliation or sanctions) and then be punished again in the state system, without formal recognition that the first process has already addressed the harm.

Inquiries such as the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody have documented deep structural inequalities, cultural alienation and barriers to justice for First Nations peoples.

Community-engaged sentencing, problem-solving courts and locally led mediation initiatives demonstrate how the two rivers can be brought closer together without erasing their distinct sources of authority.

Australia shares important features with other Australasian jurisdictions, yet also stands apart in its lack of a national treaty settlement and its particular configuration of common law and federalism.

Compared with Aotearoa New Zealand, for example, Australia has moved more cautiously in recognising First Peoples’ rights through formal instruments. Whereas the Treaty of Waitangi provides a foundational reference point in New Zealand, Australian developments have centred on judicial recognition of native title and incremental legislative reform.

The Australian case therefore highlights both the possibilities and the limits of judicially driven change in the absence of a negotiated constitutional settlement. It underscores the importance of Makarrata processes — Voice, Treaty and Truth — if the two rivers are to flow alongside one another on a more equal footing.

The Australian case also turns on contrasts between Indigenous customary approaches to justice and mainstream Western mediation models.

| Feature | Indigenous customary approaches | Australian / Western mediation model |

|---|---|---|

| Core purpose | Restore harmony, reconcile relationships and uphold group cohesion grounded in kinship and Country. | Resolve a discrete dispute between individuals, protecting rights and interests within a legal framework. |

| Third-party role | Elders or recognised leaders with cultural authority; impartial in their concern for the whole community, but not socially “neutral”. | External neutral mediator, accredited and required to remain detached from substantive outcomes. |

| Process style | Public, narrative and often ceremonial, embedded in the life of the community. | Private, structured and staged, often in offices or court-adjacent settings. |

| Communication | Story-based, relational and often indirect; silence may signal respect or reflection rather than agreement. | Direct, verbal, interest-based; emphasis on explicit articulation and negotiation. |

| Outcomes | Consensus validated by community, apology, restitution and reintegration. | Written settlement agreement enforceable in or alongside the formal legal system. |

Working at the confluence of the two rivers demands more than technical mediation skills. It requires cultural humility, careful listening and a willingness to adapt standard Western models.

Practitioners must treat cultural competence as an ethical obligation. This includes informed not-knowing, awareness of one’s own assumptions and a readiness to seek guidance from community leaders and Elders. Without this, well-intentioned interventions can unintentionally undermine both customary authority and access to state-based rights.

It is also essential to recognise that “the parties” in an Aboriginal dispute may extend far beyond the named individuals. Kinship obligations, responsibilities to Country and broader community relationships all need to be considered in the design of any process.

Community-led initiatives in Australia demonstrate how the two rivers of justice can be brought together in practice, with measurable benefits for safety and well-being.

The Mawul Rom project revitalises ceremonial reconciliation to address serious conflict, training cross-cultural mediators in processes grounded in Yolŋu Law and spiritual healing. It illustrates the potential of models that are initiated and led by First Nations communities themselves.

Outcomes include strengthened relationships between Aboriginal and non-Indigenous participants, as well as practical agreements that are culturally legitimate and durable.

In Yuendumu, a Warlpiri-led mediation and justice committee has significantly reduced local conflict and incarceration by resolving disputes within a community-owned framework. Evaluations indicate a positive social and economic return on investment.

This model highlights the value of supporting locally grounded systems rather than relying solely on distant courts and prisons to manage conflict and harm.

Integrates ceremony, apology and narrative with facilitated dialogue to resolve serious disputes. Outcome: culturally legitimate agreements and strengthened cross-cultural relationships.

Community-based mediators address local conflicts and work alongside, but not under, state institutions. Outcome: reduced violence and offending, improved community safety, and documented economic benefits.

The Australian case shows both the resilience of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Laws and the limits of recognition within a common-law state that has yet to settle questions of sovereignty and treaty.

Legal pluralism in Australia is not an anomaly but the everyday reality for many First Nations communities. Customary law continues to regulate relationships, obligations and conflict, even where it is not formally recognised by statute or precedent. State institutions, meanwhile, exert powerful influence through courts, policing and corrections.

Hybrid and community-led systems — from specialist courts to locally designed mediation initiatives — point to a future in which the two rivers of justice can flow alongside one another more respectfully. National conversations about Voice, Treaty and Truth build on these principles, seeking pathways for Makarrata that honour both Indigenous and state authority.

For practitioners, the task is to walk carefully between these rivers: upholding rights and safeguards while listening deeply to Country, kinship and Law, and recognising the authority of Elders and communities in shaping just outcomes.