Tribal and regional identities

Clan and regional affiliations anchor identity, pride and political life. They provide solidarity but can also drive conflict when groups compete for resources or influence.

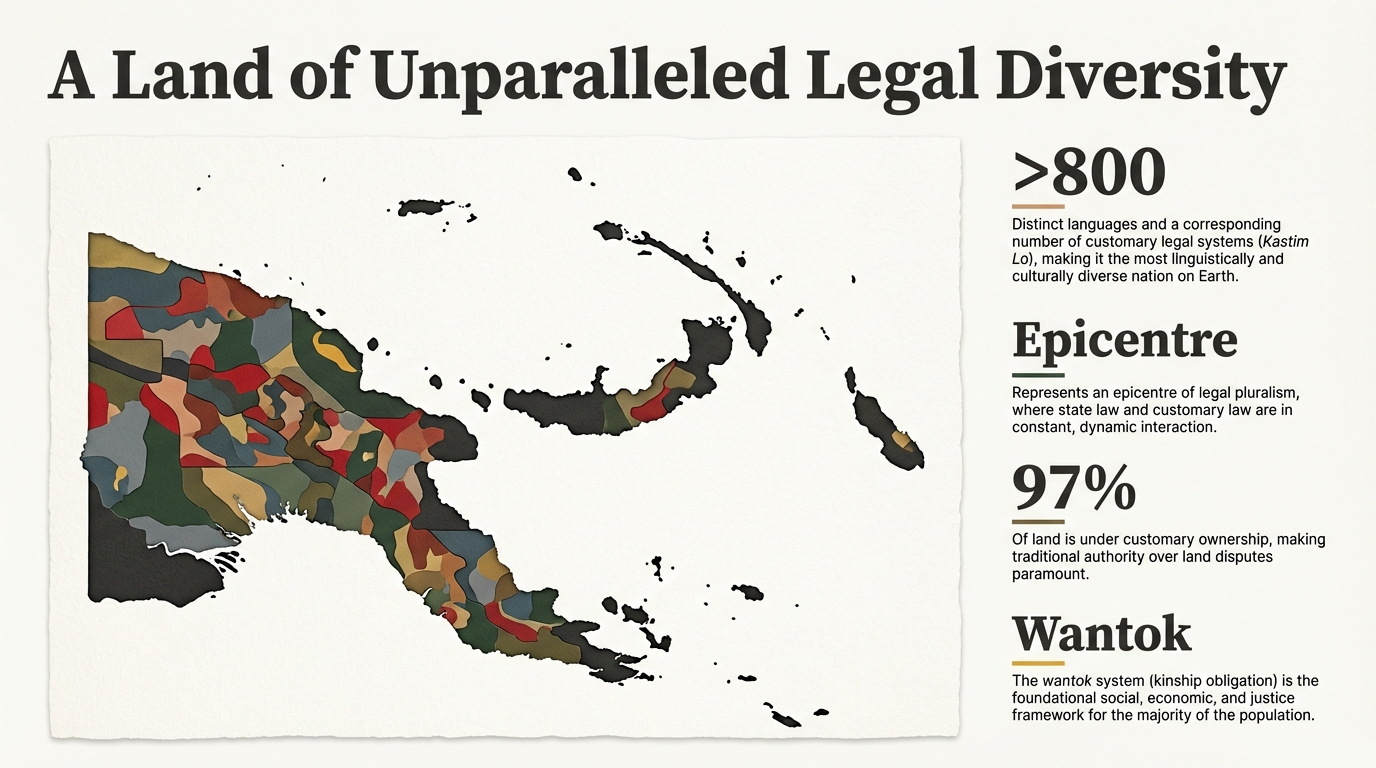

Papua New Guinea is a centre of legal diversity, where Kastim Lo – the body of custom, rules and relationships – flows alongside a Western-style state legal system. Everyday justice is shaped by both rivers.

With more than 800 languages and countless local cultures, there is no single PNG customary law. Instead, Kastim Lo is a mosaic of locally grounded systems, each tied to land, lineage and story.

Customary authority governs most everyday disputes and land dealings, especially in rural areas. Formal courts and ADR schemes operate alongside these practices, creating a highly plural legal environment.

Understanding how these systems relate is essential for anyone designing or facilitating dispute resolution processes involving Papua New Guineans, whether in PNG itself or in the region.

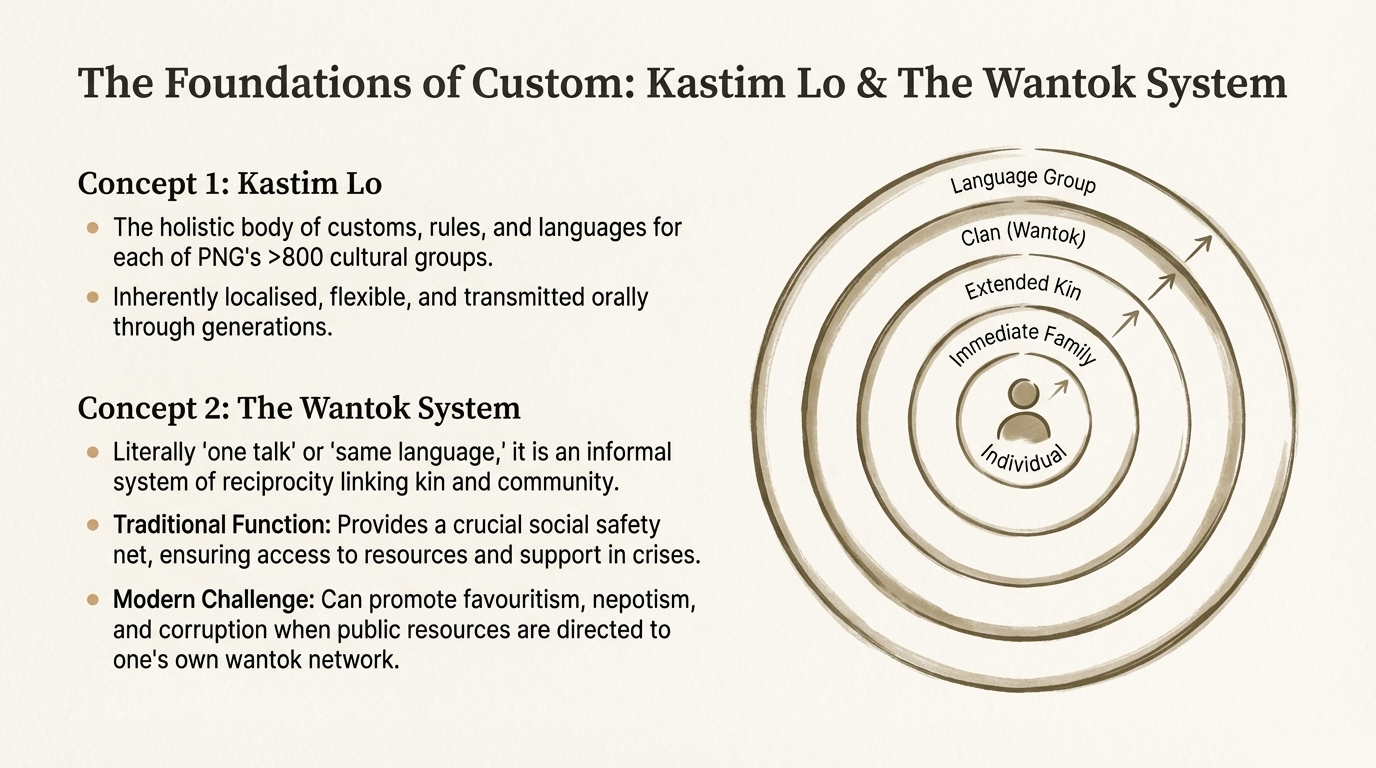

Conflict and its resolution in PNG are shaped by overlapping systems of obligation, leadership and identity: Kastim Lo, the wantok network and traditional bigman leadership.

Kastim Lo is the local body of customs and rules for each cultural group, passed down orally and adapted over generations. The wantok system links people who share language and kinship into networks of mutual support and reciprocal duty.

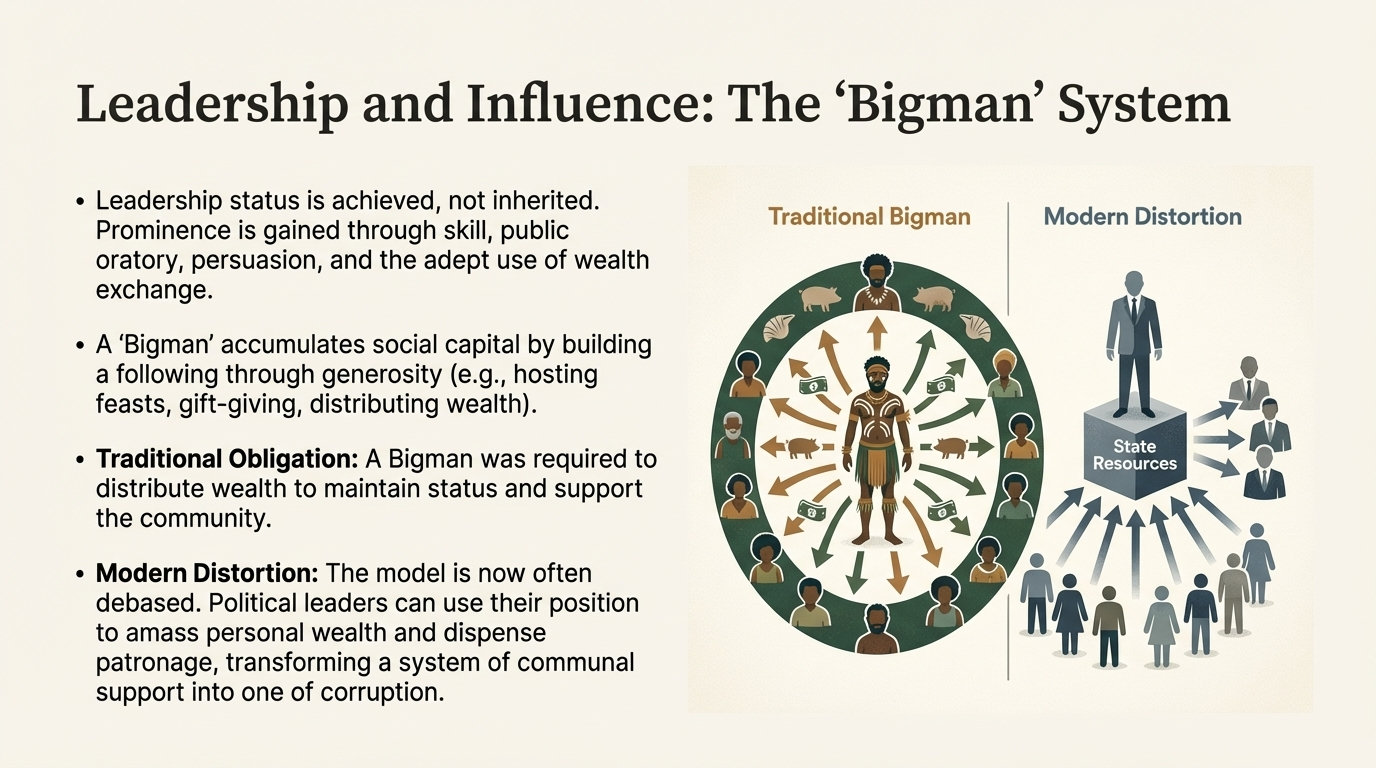

Traditionally, bigman status is earned rather than inherited. Leaders gain authority by persuasive speech and by redistributing wealth through feasts, gifts and assistance, building a network of reciprocal loyalty.

When this model is distorted, modern political bigmen may capture state resources and turn communal obligation into patronage and corruption.

Clan and regional affiliations anchor identity, pride and political life. They provide solidarity but can also drive conflict when groups compete for resources or influence.

Beliefs around spirits, ancestors and sorcery (sanguma) shape understandings of misfortune and harm, and therefore who is held responsible when things go wrong.

Under Kastim Lo, the primary aim of dispute resolution is to restore harmony within and between wantok groups, not to impose punitive sanctions on isolated wrongdoers.

Emotional harm and disrespect are often treated as seriously as physical damage, because they threaten the cohesion of the group.

Many conflicts are first taken to informal moots or wari courts. Elders and other respected figures facilitate dialogue and encourage early, local repair.

Authority comes from respect, wisdom and knowledge of custom, not from state accreditation. These leaders often act as both mediators and guarantors of any settlement reached.

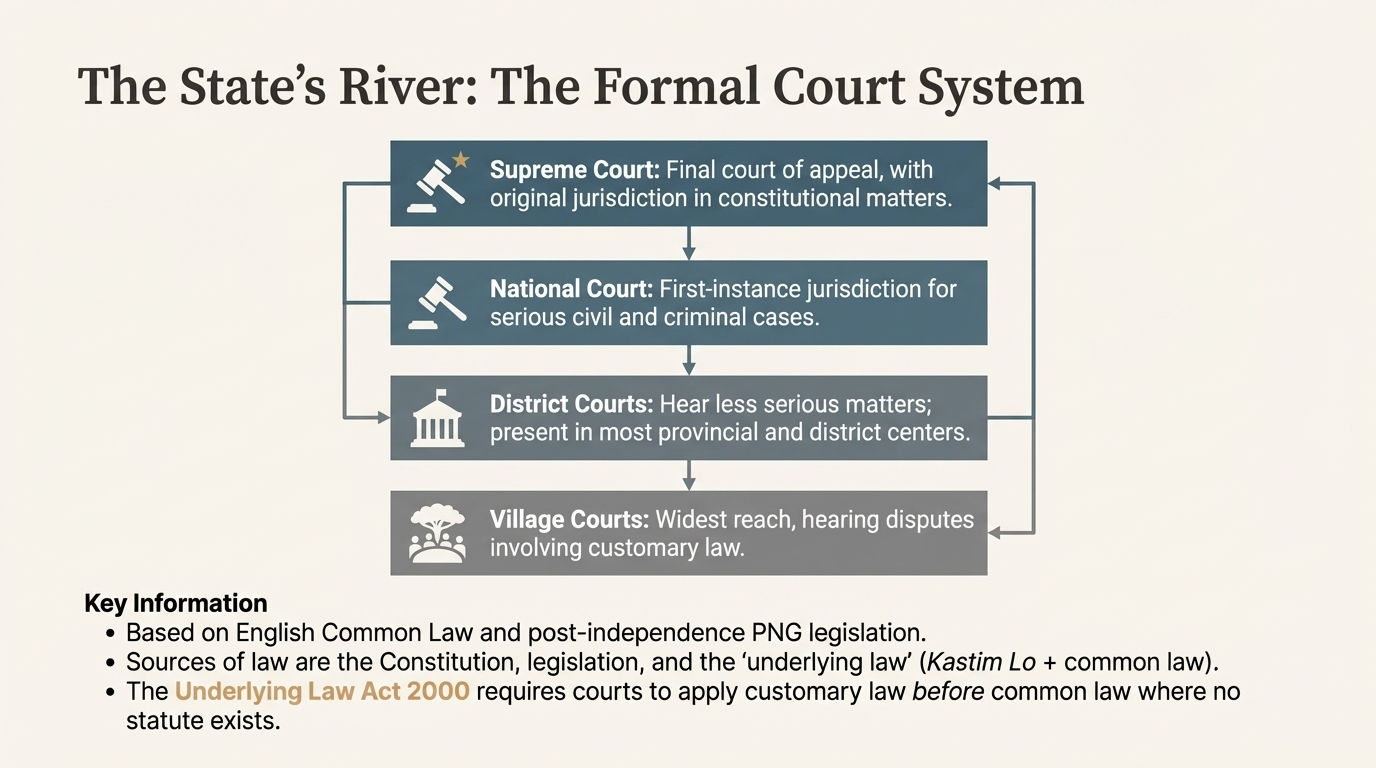

PNG’s state system combines English common law with post-independence legislation. Courts operate in a hierarchy, but for many people the Village Court is the most important justice forum.

The Supreme Court and National Court deal with constitutional, serious civil and criminal matters. District Courts handle less serious disputes. Village Courts have the widest reach, hearing local conflicts that often involve custom.

The Underlying Law Act 2000 requires courts to take account of customary law where no statutory rule applies, reinforcing the formal role of Kastim Lo.

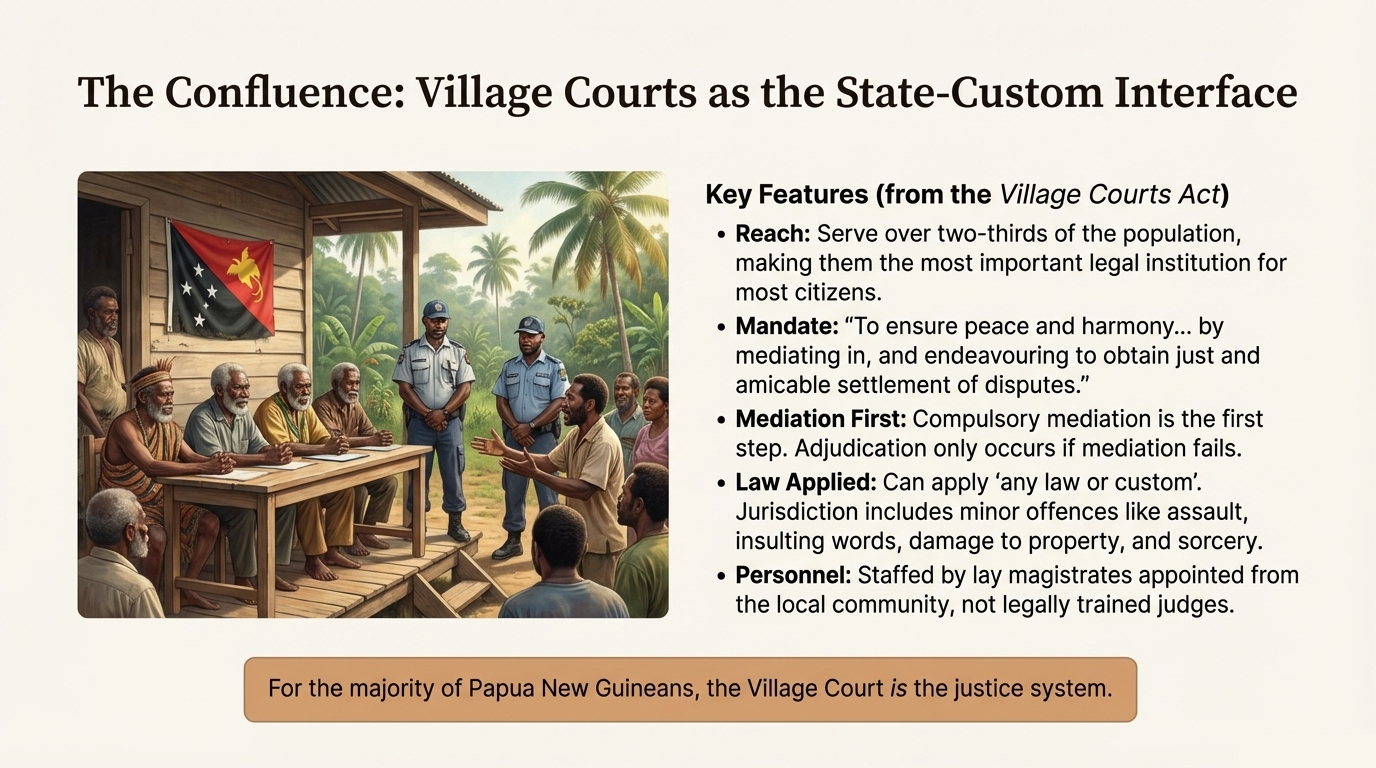

Village Courts were designed as the main interface between custom and state law. Their mandate is to ensure peace and harmony by mediating disputes, applying local custom wherever appropriate.

While PNG law explicitly recognises custom, serious tensions remain, particularly around individual rights, gender, impartiality and due process.

Village Courts blend state symbols with customary goals, using the authority of the state to reinforce consensus and compromise at community level.

Wantokism and bigmanism can drift into nepotism and corruption when they are harnessed to modern political and administrative power.

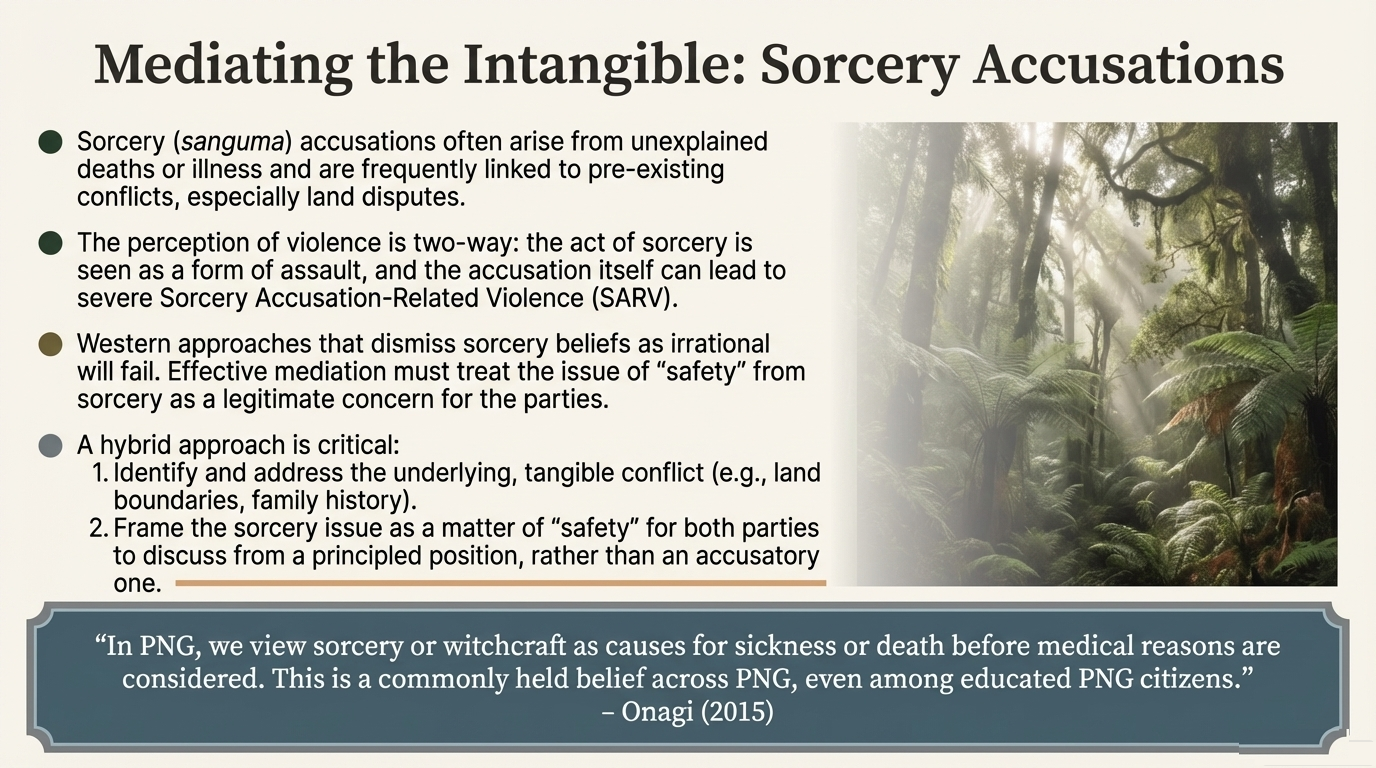

Accusations of sorcery (sanguma) can lead to serious violence and human rights abuses. Addressing these disputes requires engaging with spiritual beliefs while upholding criminal law protections.

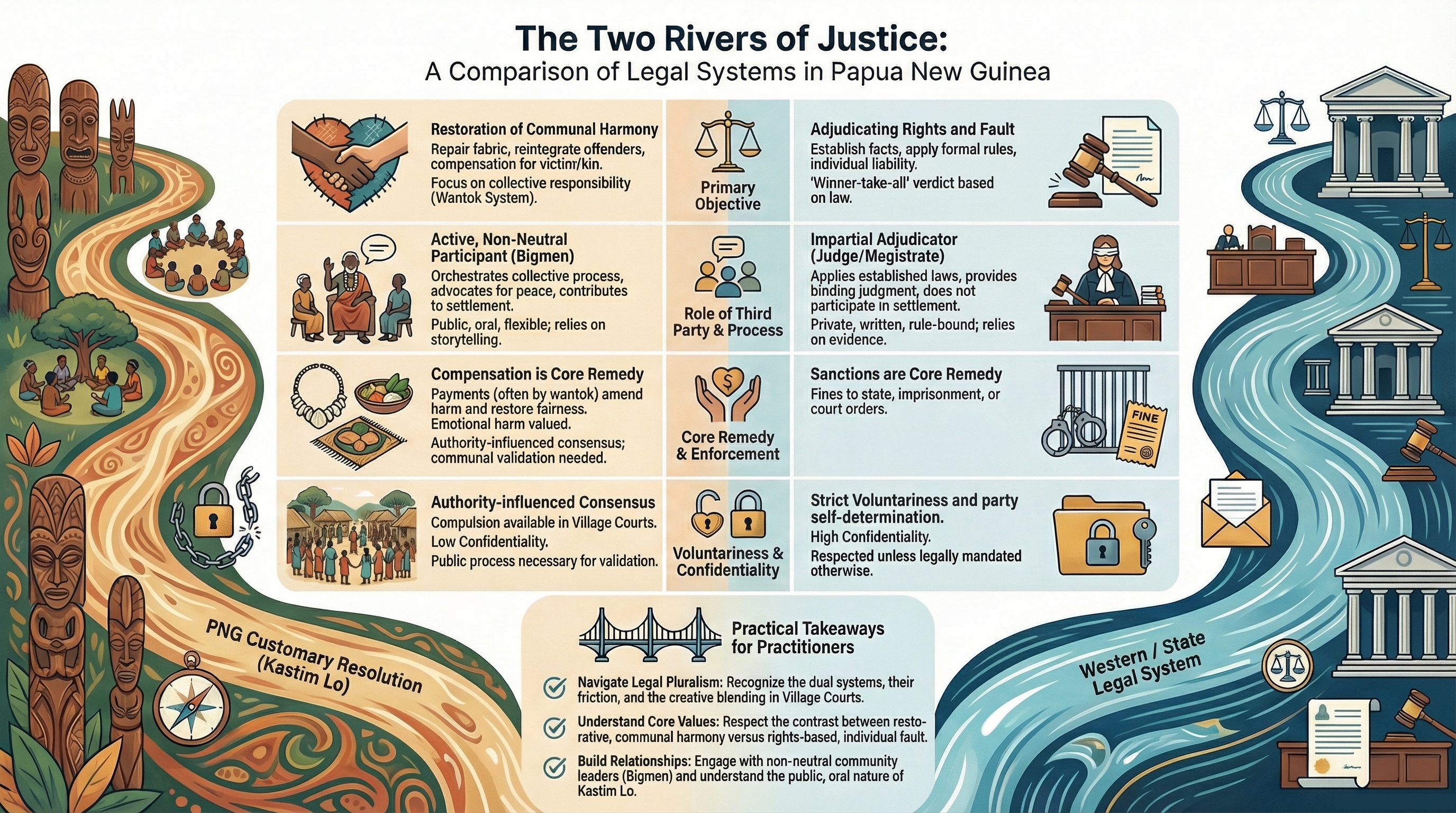

Practitioners must navigate not just two institutions but two philosophies: PNG customary resolution (Kastim Lo) and Western-style adjudication and mediation.

| Feature | PNG customary resolution (Kastim Lo) | Western / Australian mediation |

|---|---|---|

| Primary goal | Restore communal harmony, repair relationships, reintegrate offenders, satisfy victim’s kin. | Reach an efficient, rights-based settlement between individual parties; finality of agreement. |

| Third party role | Active, non-neutral participants (bigmen, elders, Village Court magistrates) who advocate for peace and may help shape outcomes. | Impartial, external mediator who manages process but does not advise or decide. |

| Process style | Public, oral, flexible; relies on storytelling and community participation; often held in open forums. | Private, confidential, time-bound; follows a structured sequence of stages. |

| Core remedy | Compensation, apology and other restorative acts, funded and guaranteed collectively. | Written settlement terms focused on rights and obligations of the immediate parties. |

| Voluntariness & confidentiality | Authority-influenced consensus; public validation is often key to enforcement. | Strict voluntariness, party self-determination and legal confidentiality. |

Imposing a rigid Western model can be an act of cultural harm. Effective practice requires a hybrid approach that works with, rather than against, PNG social realities.

When a process ignores wantok networks, Kastim Lo and spiritual beliefs, it can cut parties off from their support systems and undermine the very conditions needed for compliance and healing.

The task is not to export a single model but to co-design processes with local partners that protect safety while respecting community authority.

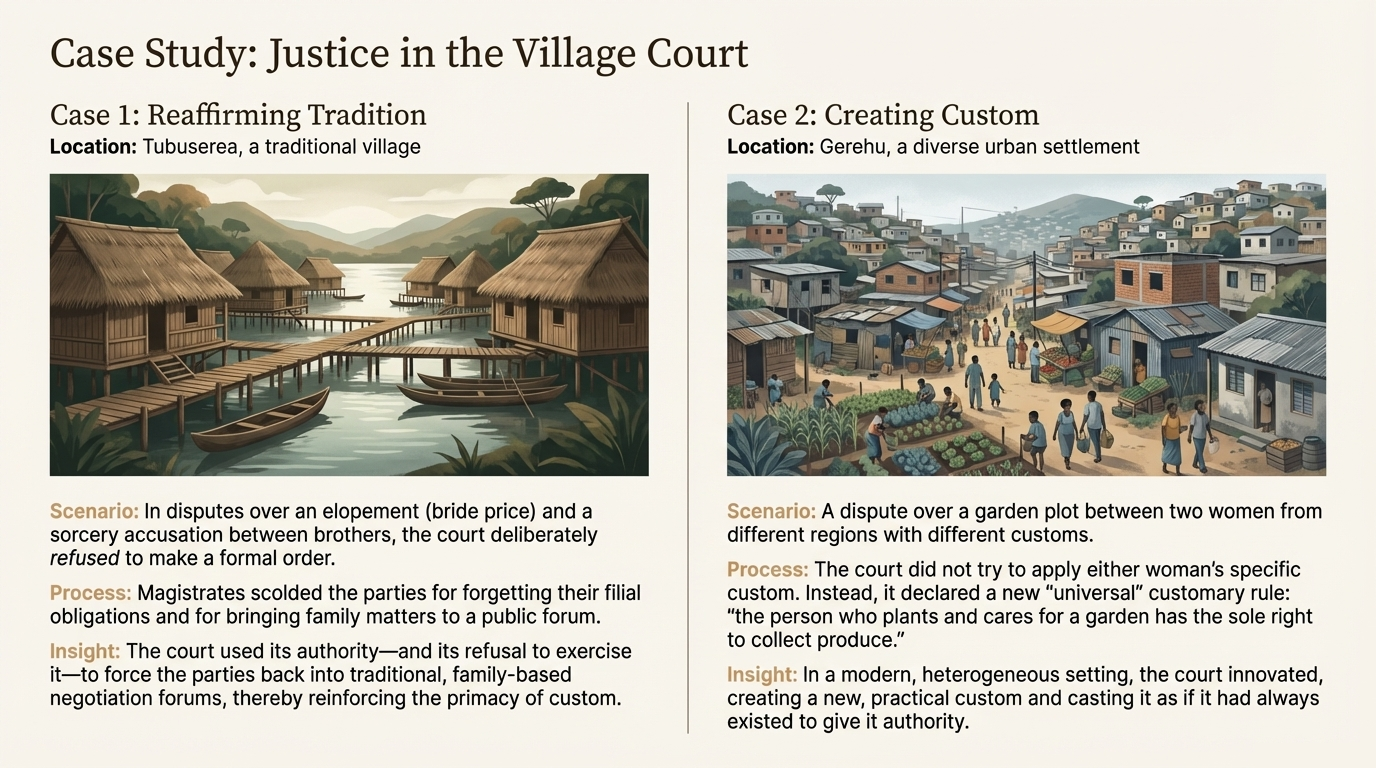

Case studies from Tubuserea and Gerehu illustrate how Village Courts and local leaders actively shape outcomes while keeping custom at the centre.

In one case, magistrates refused to make a formal order in an elopement and sorcery dispute, forcing parties back into traditional negotiations and reinforcing family-based obligations. In another, a new shared rule for an urban garden dispute was created and accepted as if it had always been custom.

These examples show how Village Courts use state authority to nurture, rather than replace, customary solutions.

Sorcery accusations are often linked to unexplained deaths or land conflicts. Parties may see both the alleged sorcery and the accusation itself as forms of violence. A hybrid approach treats parties’ safety concerns seriously while locating the underlying disputes over resources and relationships.

Effective mediators frame sorcery as a shared safety problem, not a question of belief to be judged.

PNG shows what it means for custom and state law to engage each other continuously, not as rivals to be ranked, but as rivers that can be braided together.

Customary law has not disappeared under state law; it has adapted, engaging with courts, ADR rules and development projects to create hybrid forms of justice that remain deeply local. Village Courts are a key site of this innovation, blending state symbols with customary goals of reconciliation.

For practitioners, humility and adaptability are indispensable. Durable outcomes depend on processes that honour Kastim Lo, work with wantok networks and address emerging issues such as corruption and sorcery-related violence without dismissing the beliefs that underlie them.

The goal is not for one river to absorb the other, but for both to flow together in a stronger braided river of justice that is distinctly Papua New Guinean.