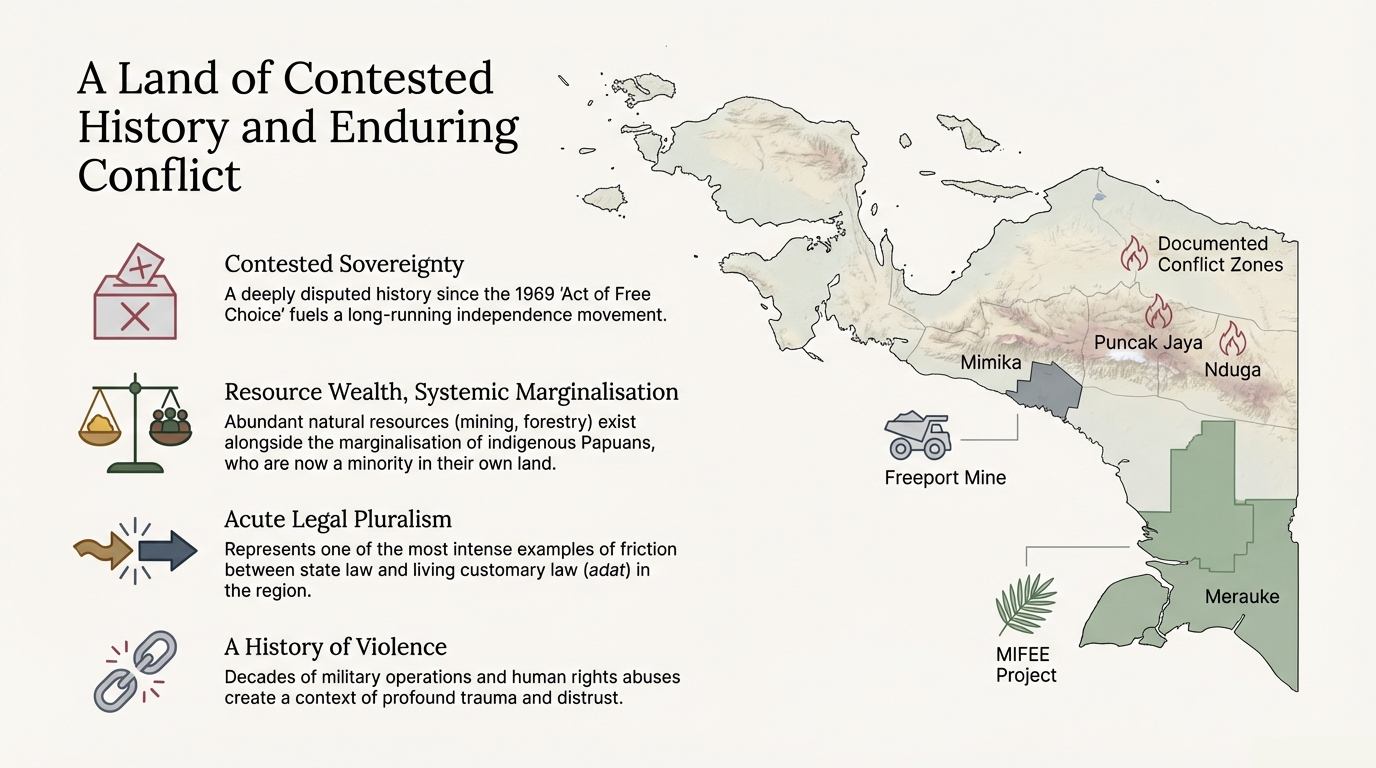

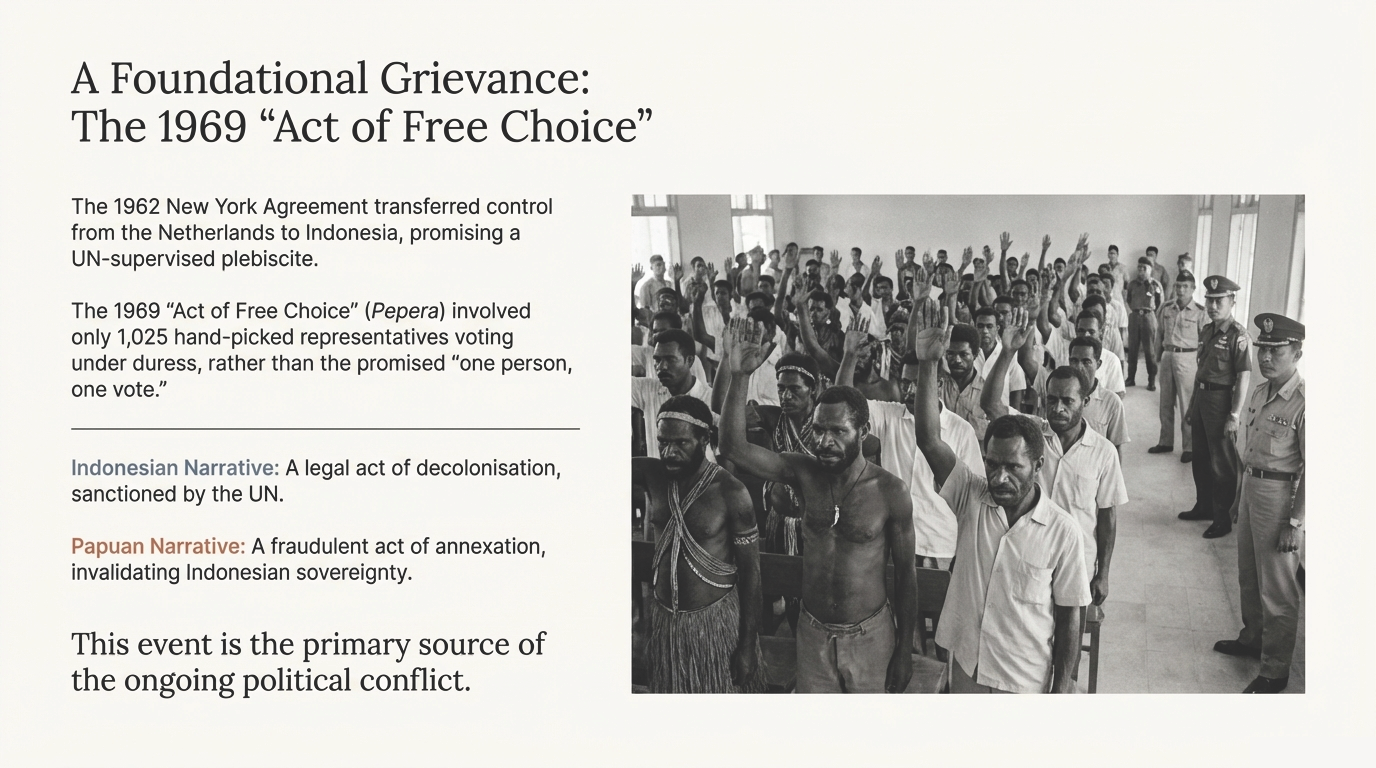

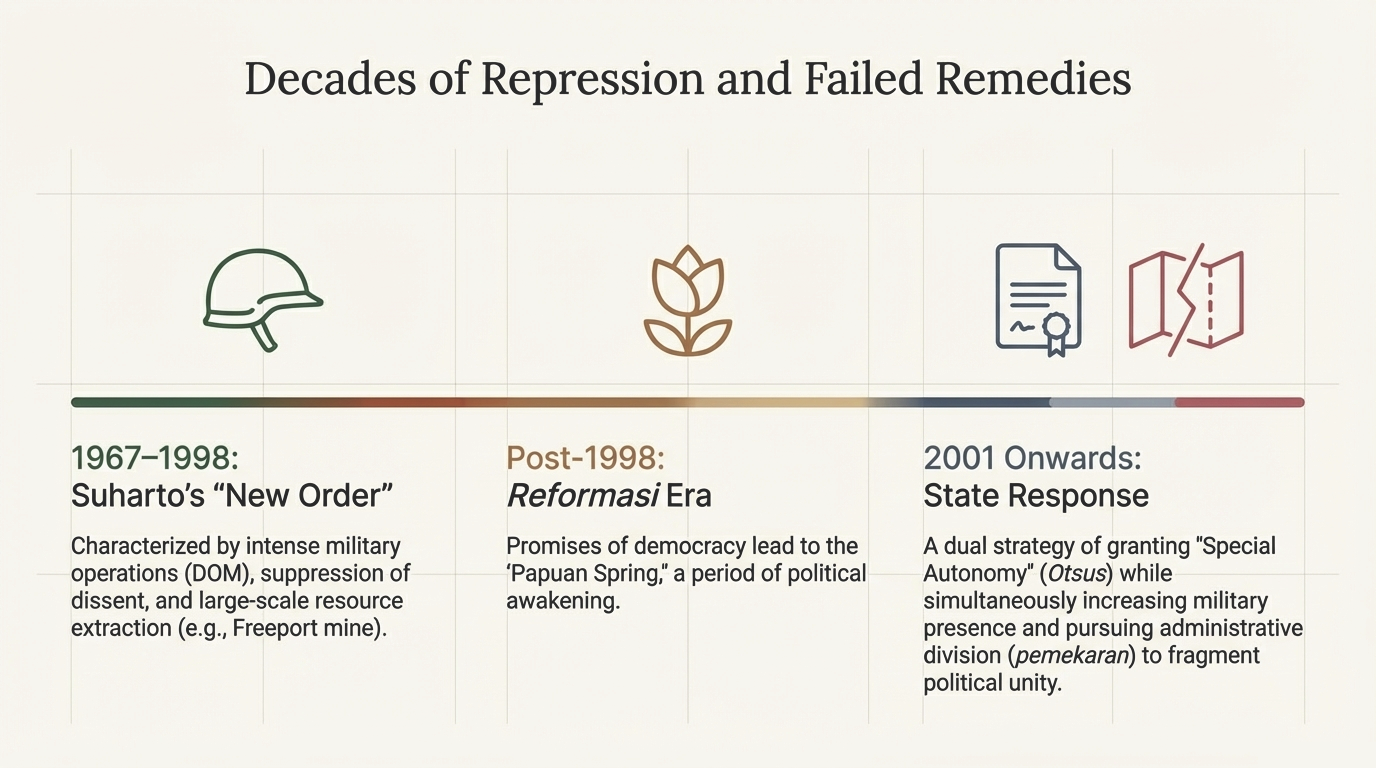

The region was formally integrated into Indonesia following the controversial 1969

“Act of Free Choice”. Since then it has been marked by persistent demands for

self-determination, human rights concerns and deeply rooted grievances about

racism, land dispossession and political marginalisation. The 2001 Special

Autonomy Law (OTSUS) was meant to resolve these issues by devolving authority

to provincial government, but two decades on many Papuans view it as a failed

promise.

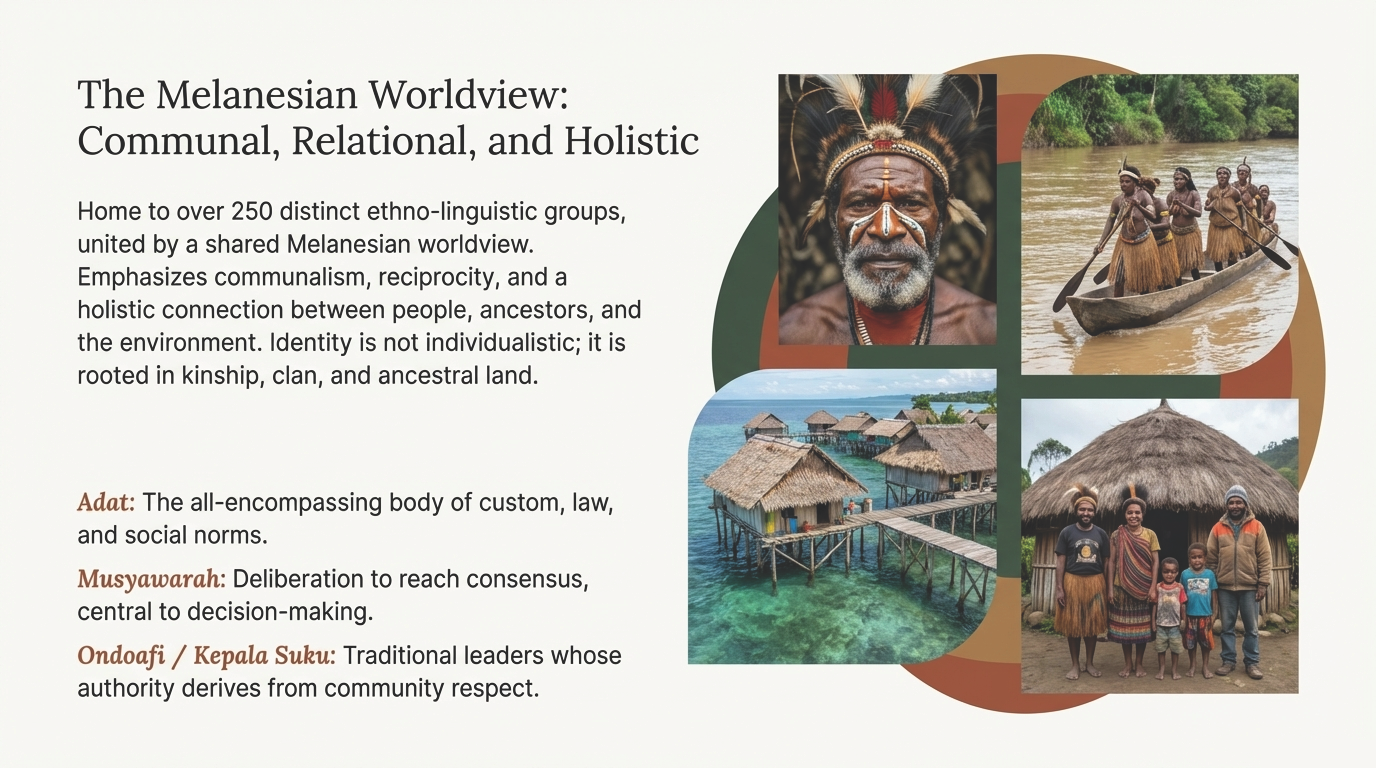

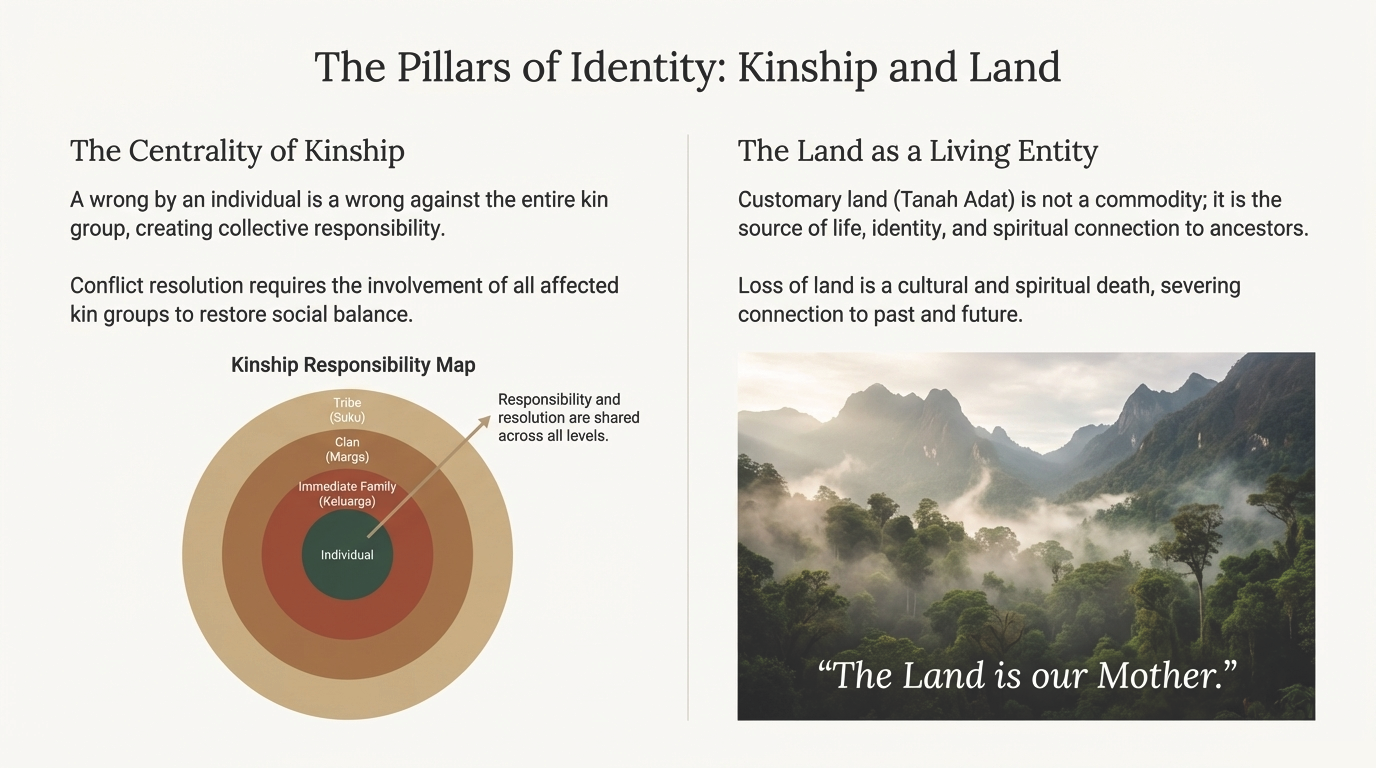

For dispute resolution practitioners, Indonesian Papua presents a complex picture:

robust customary (adat) systems of justice – centred on elders, kinship and the

spiritual significance of land – operate in parallel with a centralised state system

of courts, police and administrative law. Understanding these “two rivers” of law

is essential for any meaningful engagement with Papuan communities.

Note on terminology:

This page uses “Indonesian Papua” to refer to the territories commonly known as

Papua and West Papua. The term “Papuan” is used for indigenous Melanesian

communities, whose values, identities and legal traditions span administrative

boundaries.